Fish living in the “twilight zone” have a greater biomass than previously thought.

By James Keegan, RJD Intern

Mesopelagic fish, fish living at depths between 200 and 1000 meters in the ocean, reside in water with very low levels of light. Although they are typically small, mesopelagic fish constitute the largest biomass of fish in the world because of their immense numbers. Previous estimates state that there are about 1,000 million tons of mesopelagic fish worldwide. However, using data collected on the Malaspina 2010 Circumnavigation Expedition, Irigoien et al. 2014 show that there are about 10 times more mesopelagic fish than previously estimated. Such an increase in an already massive fish community alters how we determine the role mesopelagic fish play in ocean food webs and chemical cycling.

A man holding the mesopelagic species Stenobrachius leucopsaurus. It belongs to a family of fish commonly known as the lanternfish. (Occidental College. url: http://www.oxy.edu/sites/default/files/assets/TOPS/Lampfish25.jpg)

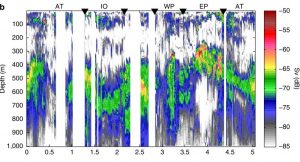

Previously, scientists pulled nets behind their boats in a process called trawling in order to capture fish and estimate their populations. This process is not efficient in catching mesopelagic fish and leads to an underestimation of their numbers. Instead of trawling, scientists aboard the Malaspina 2010 used an echosounder, a type of SONAR, to determine the biomass of mesopelagic fish. In this method, the echosounder emits a pulse of sound into the water and records the sound that returns after bouncing off an object. Using sound to weight ratios previously determined in other studies, Irigoien et al. 2014 were able to estimate the mesopelagic fish biomass from the recorded acoustic data. Irigoin et al. 2014 then used food web models to corroborate the estimate given by the acoustic data. Their estimates determined the mesopelagic biomass to be about 10-15,000 million tons, about 10 times higher than previous estimates.

Caption: Acoustic data collected on the Malaspina 2010. The top of the figure represents the surface of the ocean, and the bottom of the figure represents a depth of 1000 meters. The colors in the figure show where sound bounced off marine organisms and returned to the echosounder. Between 200 and 1000 meters, the organisms are mostly mesopelagic fish. The black triangles indicate the border between ocean basins. AT stands for Atlantic Ocean, IO for Indian Ocean, WP for Western Pacific, and EP for Eastern Pacific. (Irigoien et al. 2014)

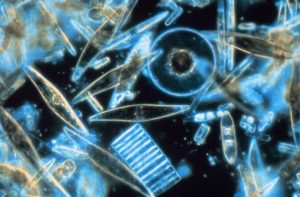

Irigoien et al. 2014 also found that mesopelagic biomass is closely tied to the plankton, miniscule, floating organisms of the ocean, that undergo photosynthesis. These photosynthetic plankton form the base of the marine food web, and other, larger plankton consume them. Mesopelagic fish then feed on these herbivorous plankton.

A photo of diatoms, photosynthetic plankton, under microscope. (Wikipedia. url: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Diatoms_through_the_microscope.jpg)

In the open ocean, where nutrients are poor, herbivorous plankton do not efficiently capture photosynthetic plankton. This implies that fish will not efficiently obtain their energy, which ultimately comes from the photosynthetic plankton. However, Irigoien et al. 2014 contest that the transfer of energy to the mesopelagic fish is more efficient in the open ocean because the water is warm and clear, allowing the visual fish to more easily capture their prey. Considering this argument, Irigoien et al. 2014 determined that mesopelagic fish may be using about 10% of photosynthetic plankton for energy.

Irigoien et al. 2014 showed that the biomass of mesopelagic fish, as well as their usage of energy in the open ocean food web, is much greater than previously thought. Due to the impact these two findings would have on ocean ecosystems and chemical cycling within them, scientists must make further and more accurate investigations regarding the mesopelagic fish community.

References:

Irigoien, Xabier, T.A. Klevjer, A. Røstad, U. Martinez, G. Boyra, J.L. Acuña, A. Bode, F. Echevarria, J.I. Gonzalez-Gordillo, S. Hernandez-Leon, S. Agusti, D.L. Aksnes, C.M. Duarte, S. Kaartvedt (2014) Large mesopelagic fishes biomass and trophic efficiency in the open ocean. Nature Communications 5, Article number: 3271 doi:10.1038/ncomms4271