Assessing the effectiveness of specially protected areas for conservation of Antarctica’s botanical diversity

By Shannon Moorhead, SRC Intern

When one thinks of Antarctica, the first things that come to mind are frigid, icy weather and penguins. Therefore, it may come as a surprise to many that Antarctica is home to a variety of plant communities. Only 0.34 % of the Antarctic continent, and approximately 3% of the Antarctic Peninsula and offshore islands, is free of the snow and ice covering that transforms the remainder of the continent into a frozen wasteland. Only a small fraction of the ice-free land is able to support plant life: most of it is high latitude desert, rock faces protruding out of the ice sheets, and high altitude mountain ranges. This confines most visible terrestrial life to the coasts, predominantly along the Eastern coastline, the Antarctic Peninsula, and the Scotia Arc archipelagos.

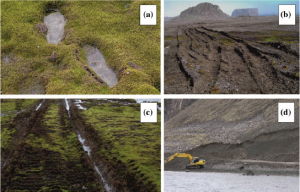

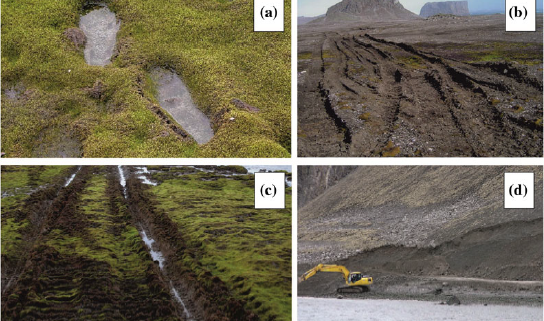

Antarctic vegetation and the damage caused to it by human activity. A) Moss and footprints b) Tire tracks through vegetation c) Vehicle tracks in moss d) Quarrying (Hughes et al., 2015)

Even the most diverse parts of Antarctica have relatively little botanical biodiversity compared to other ecosystems. The majority of Antarctic primary producers are cryptogams, seedless autotrophs that generally grow low to the ground, such as mosses, lichens, and liverworts. There are only two vascular plant species native to the continent. In addition to true plants, Antarctica is home to substantial microflora communities consisting of fungi, algae, and cyanobacteria. Vascular plants and bryophytes (nonvascular plants like mosses and liverworts) inhabit primarily coastal areas while inland and areas with high elevation are dominated by microfloral communities and lichens. These colonizable sites devoid of ice are few and far between, often separated by stretches of ocean or ice that can be hundreds of kilometers long. Isolation to this extent hinders the ability of plant species to colonize new land, restricting them to specific areas. This separation has prevented gene flow between distinct Antarctic plant communities, evolutionarily isolating them; in other words, these communities will continue to grow and adapt on their own, with the potential to eventually develop into distinct species. The regional disparities in terrestrial biodiversity make it very easy to divide the continent into specific biogeographic regions; 15 Antarctic Conservation Biogeographic Regions (ACBRs) have been identified to provide a formal structure upon which to develop a conservation plan for Antarctica and the organisms that inhabit it.

As human activity on Antarctica increases, it is becoming more apparent that an effective conservation strategy for the continent is necessary. Construction, overland transport, and continuing operation all threaten terrestrial organisms, especially those inhabiting coastlines, where most tourist and research practices are focused. Humans may also introduce invasive species, which could have detrimental effects on indigenous botanical biota. Plant communities are also facing destruction at the hands of fur seals, whose expanding range has increased the amount of vegetation they trample and damage in the Antarctic Peninsula. In addition to the threats affecting Antarctic plants in the immediate future, climate change has the potential to directly impact the continent’s flora.

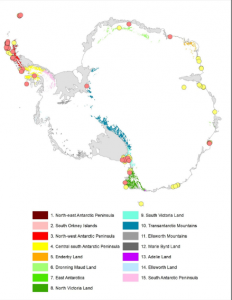

Map of ASPAs. Red circles denote vegetation specific ASPAs, yellow are ASPAs not included in this study (Hughes et al., 2015).

Due to the scarcity and low diversity of Antarctic vegetation, these threats could cause severe damage, possibly wiping out entire communities or species in extreme scenarios. Recognizing the need for protection, the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty instrumented Antarctic Specially Protected Areas (ASPAs) to maintain the diversity and health of representative Antarctic ecosystems. However, the effectiveness of this system is questionable; only 1.5 % of Antarctica’s ice-free terrain is under the jurisdiction of ASPAs and there are multiple regions with no ASPAs at all. 33 of the 72 established ASPAs specifically note protecting plant diversity as a management goal. Yet, these ASPAs include less than 0.5% of Antarctica’s ice-free ground and less than 16.1 km2 of vegetation cover. This is most likely only a small fraction of the continent’s botanical life, given a 2011 study that estimated 44.6 km2 of the northern Antarctic Peninsula alone has greater than 50% probability of vegetation presence. Another marked problem is that 96% of protected ice-free ground is within 2 ACBRs. This offers great protection for those habitats, but does not do an effective job of preserving diversity by concentration on only one or two ecosystems. It is blatantly apparent that Antarctica’s management strategies must be reworked in order to properly conserve both the health and diversity of its ecosystems.

Hughes KA, Ireland LC, Convey P, Fleming AH (2015) Assessing the effectiveness of specially protected areas for conservation of Antarctica’s botanical diversity. Conservation Biology 00: 1-8

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!