The Effect of Materialism on Ecotourism Attitudes, Interest, and Intention

By Dana Tricarico, SRC Intern

The term “ecotourism” has been widely used since the late 1980s and has become a major niche in not only the tourism sector itself, but also in tourism studies (Weaver and Lawton, 2007). Traditional approaches to conserving biodiversity in ecologically important areas have proved to be ineffective due to conflicts between park authorities implementing conservation laws and the local people to those protected areas. Ecotourism has provided a solution to this problem by combining protection of areas with cooperation from the local people so that these people feel empowered and a part of the management decisions (Lai and Nepal, 2006). Despite the positives of this form of tourism, especially in places like small island destinations, which are known for their unique cultures and remoteness, there are still challenges with implementing this replacement to mass tourism. First and foremost, local authorities need to not only see the potential for tourism in these particular locations, but they must provide strong leadership to maintain the community’s engagement and continue to empower the local people. Many governments feel pressured to join the pattern of traditional mass tourism by building large resorts which causes them to lose sight of how rewarding it can be to have sustainable forms of tourism instead (D’Hauteserre, 2015). Researchers Allan Cheng Chieh Lu et. al (2014) decided to look at ecotourism from a different angle. Rather than the implementation, they investigated the traveler aspect of ecotourism.

A native of French Polynesia demonstrates sustainable tourism by leaving a low environmental footprint when making cloths and souvenirs with strips of tapa. (Hauteserre)

This particular study looked at how materialism influences ecotourism attitude, ecotourism interest, ecotourism intention as well as the willingness to pay a premium for ecotourism. In order to capitalize on the values that ecotourism promotes and to try and fix the issues associated with it, this type of research is important to see the values that may influence travelers and their opinions about taking part in ecotourism. Materialism, i.e., the emphasis people place on the satisfaction of life from their possession of material goods, is very prominent in the western society and has been increasing for decades. Therefore, this thought process is important in tourism studies because it can conflict with environmental conservation, a major component of ecotourism. This is because environmental conservation often goes hand in hand with decreasing overconsumption and recycling old goods.

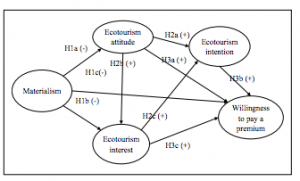

The beginning stages of this research entailed a literature review, which was done to create hypotheses based on prior research. After doing so, a conceptual framework was created to show their findings. The study itself was done by collecting data from 2,352 Italian travelers using an online self-administrated questionnaire. The survey had seven sections, six of which measured different concepts with the seventh measuring the demographics of the respondents. To measure ecotourism interest, ecotourism attitude, and willingness to pay a premium, the respondents were given statements related to each of those topics being measured and then asked to rank them. This scale was from 1-7 with 1 representing that statement was not important to them, and 7 representing that it was very important to them. To interpret the results, statistics were used using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS).

Conceptual framework for the study by Lu et. al which organizes determinants of ecotourism behavior into five categories. This was created by putting together literature reviews and creating nine hypotheses based on this framework (Lu)

The results showed that high value for materialism can negatively influence ecotourism attitude, ecotourism interest, and willingness to pay a premium for eco-tourism products. This is in line with previous research done by Porritt (1984) which explained that a great deal of the issues involved with the global environmental decline is because of materialism. The findings also concluded that, due to the cognitive dissonance associated with having a high desire for material possessions but also wanting to help with environmental issues through eco-tourism, may result in eco-tourism appearing as an unattractive type of leisure.

The conclusions from this study provide practical implications for ecotourism operators as it highlights the necessity to use forms of communication to increase the amount of positive attitudes toward ecotourism. A movement must first garner substantial support before it can truly make an impact, however. For example, ecotourism operations and service providers would need to emphasize the importance of preserving the environment and culture within specific regions through events, media outlets, and advertisement, while at the same time demonstrating the benefits to the local community and the individuals visiting the community (Lu, 2015). There are many challenges that affect the success of not only implementing ecotourism, but also to catering to the tourists who are highly materialistic. With extensive long-term commitment to educating highly materialistic people about the importance of preserving the environment, however, ecotourism can prove to be extremely beneficial for visitors, locals, and the environment alike.

Works Cited

Porritt, J. (1984). Seeing Green: The Politics of Ecology Explained. New York: Blackwell.

Weaver, D. B., and L. J. Lawton. (2007). “Twenty Years on: The State of Contemporary Ecotourism Research.” Tourism Management, 28 (5): 1168-79.

Dhauteserre, A.-M. “Ecotourism an Option in Small Island Destinations?” Tourism and Hospitality Research 16.1 (2015): 72-87. Web.

Lu, A. C. C., D. Gursoy, and G. Del Chiappa. “The Influence of Materialism on Ecotourism Attitudes and Behaviors.” Journal of Travel Research 55.2 (2014): 176-89. Web.

Lai, Po-Hsin, and Sanjay K. Nepal. “Local Perspectives of Ecotourism Development in Tawushan Nature Reserve, Taiwan.” Tourism Management 27.6 (2006): 1117-129. Web.