Are Marine Protected Areas Effective?

By Natalie Torkelson,

Marine conservation student

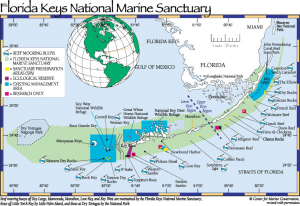

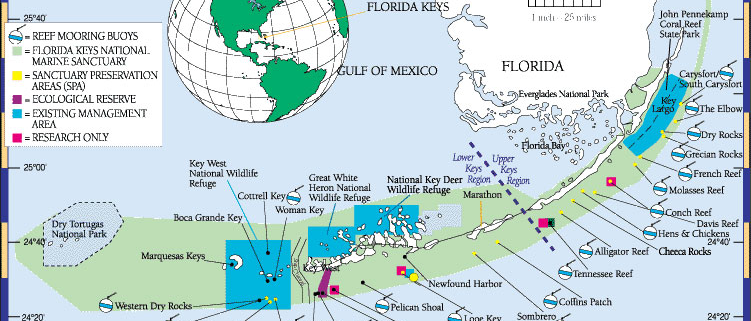

Living in South Florida, most people are familiar with the concept of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs). The Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary is just one of these protected areas in Florida. Six percent of the sanctuary consists of fully protected zones. Along with the fully protected zones, 27 management areas were designated when the sanctuary was created, and the sanctuary also includes 20 existing management areas that have been designated by other agencies (National Marine Protected Areas of the United States). Biodiversity, or the amount of different species in an area, is often used as an indicator of what areas are important and should be protected (Chapin et al., 2000). However, there is much evidence that there are other factors that should be taken into account when making decisions about what areas should be conserved. Many ecosystems depend more on functional diversity to remain healthy and productive than on the number of different species that it has (Nystrom 2006). Functional diversity is the number of different biological functions or processes in an ecosystem, and this, as well as trophic levels can be used to compare the communities in different areas. Measuring each of these things can help determine what areas are important to conserve, but are marine protected areas really effective? One study in the Mediterranean set out to answer this question by comparing the species, trophic, and functional diversity of protected and non-protected areas. The hypothesis was that species, trophic, and functional diversity were higher in protected areas than in adjacent non-protected areas (Villamor and Mikel 2012).

Map of the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary showing the different management areas.

Photo: http://www.flmnh.ufl.edu/fish/southflorida/coral/conservation.html

This study by Adriana Villamor and Mikel A. Becerro took place in August 2008 off of the coast of Spain in the Mediterranean Sea, and looked at five MPAs and also looked at non-protected areas adjacent to these MPAs. Two MPAs are located in the North and are about 30 kilometers from each other. The other three MPAs are off of the Southeast coast of Spain and are a little farther apart from each other than the MPAs in the North are. Three surveys were conducted in each of the MPAs. These surveys were carried out in three different areas within the MPA. Similarly, three non-protected areas outside of each of the MPAs were also surveyed.

During the surveys the researchers used a visual census technique to count the numbers of fishes, sea stars, sea urchins and stationary animals on the sea floor. These numbers were used to look at the species diversity in the area that was surveyed. After the different species were quantified, they were assigned to different groups based on their trophic level. These different levels were: predators, carnivores, herbivores, filter feeders, erect producers, and barren ground producers. These different groups were used to look at differences in the structure of the food web between all the areas surveyed. The species were also grouped into different categories that represented functional groups within the community. These categories were determined for species within each trophic level. For example, different species of algae were separated into groups depending on their type. So within the erect producers trophic level, categories included: filamentous, leathery, and calcareous algae, among others. These different groups were used to compare the functional diversity between all the different areas that were surveyed.

The results of the study found that the species diversity was not different when the areas inside the MPAs were compared with the areas adjacent to the MPAs. However, the species diversity was different depending on where in the Mediterranean the MPAs and their adjacent areas were located. MPAs that were located off the North coast of Spain had a different composition of species than an MPA off of the South coast of Spain had. There was a difference in the trophic diversity when protected and unprotected areas were compared. There were more top predators inside the MPAs than in the adjacent unprotected areas. Herbivores were more abundant outside the MPAs than inside the MPAs. This was true of all of the geographic areas studied, and this has been shown in other studies of MPAs as well (Friedlander and DeMartini 2002; Pace et al., 1999; Pinnegar et al., 2000). One important conclusion was that there was higher functional diversity inside the MPAs when compared to the areas outside of the MPAs. Fish functional groups were more abundant inside the MPAs than in the unprotected areas outside of the MPAs, and this was true of all of the MPAs that were surveyed. It was suggested by the authors that protection might have a bigger effect on the functional diversity of an area than on the species diversity and the abundance of these species in that area. So there was some evidence that these protected areas were indeed effective in that there was more functional diversity inside the protected areas than outside of them.

This study was comparing the trophic, species, and functional diversity between protected and non-protected areas. By comparing these things it is possible to make some inferences about the communities and the composition of these communities. Community composition and structure can be used to determine if an ecosystem is productive and healthy. High functional diversity is one indicator of a productive ecosystem. This study demonstrated that protection affects trophic levels and community structure, and implementing protected areas could help ensure that the ecosystem remains productive.

This study is encouraging because it shows that protecting an area is actually making a difference in that ecosystem. There is much more research that needs to be done to determine the best ways to implement a Marine Protected Area, and to ensure that these protected areas are actually effective. With more studies like this one, which look at community structure rather than focusing on single- species conservation, policy makers may be more efficient at designating effective protected areas. With more protected areas, ecosystems are likely to remain healthy and productive and the full benefits of the ecosystem services they provide can be utilized.

REFERENCES

Chapin FS, Zavaleta ES, Eviner VT, Naylor RL, Vitousek PM, Reynolds

HL, Hooper DU, et al. (2000) Consequences of changing biodiversity. Nature 405: 234-242

Friedlander AM, DeMartini EE (2002) Contrasts in density, size, and biomass of

reef fishes between the northwestern and the main Hawaiian islands: the effects

of fishing down apex predators. Marine Ecology Progress Series 230: 253-264

National Marine ProtectedAreas. http://www.mpa.gov/helpful_resources/florida_keys.html (accessed 3 Oct 2012)

Nystrom M (2006) Redundancy and response diversity of functional groups:

implications for the resilience of coral reefs. Ambio 35: 30-35

Pace ML, Cole JJ, Carpenter SR, Kitchell JF (1999) Trophic cascades revealed

in diverse ecosystems. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 14: 483-488

Pinnegar JK, Polunin NVC, Francour P, Badalamenti F, Chemello R,

Harmelin-Vivien ML, Hereu B, et al. (2000) Trophic cascades in benthic

marine ecosystems: lessons for fisheries and protected-area

management. Environmental Conservation 27:179- 200

Villamor A, Becerro MA (2012) Species, trophic, and functional diversity in

marine protected and non-protected areas. Journal of Sea Research 73:109-116

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!