Blue Whiting: A New Approach to Management

by Zack Good,

Marine conservation student, RJD Intern

The blue whiting (Micromesistius poutassu) is a medium-sized fish distributed throughout the northeastern Atlantic Ocean (Figure 1). It feeds mostly on zooplankton and smaller fish and also serves as prey for larger fish. As far as humans are concerned, it is a significant source of both income and food. It is important that this fishery be studied, as it is currently overexploited, much like the 88% of European fish stocks fished beyond maximum sustainable yield (Commission of the European Communities).

Sebastián Villasante studied the blue whiting fishery in Spain in his 2012 paper, concentrating on Galicia, Spain, to assess the state of the fishery from both a biological/ecological perspective and a human perspective. By synthesizing these two perspectives he is able to look at the fishery in a different way than previous fisheries management regimes have. Villasante even provides recommendations for management changes in the future.

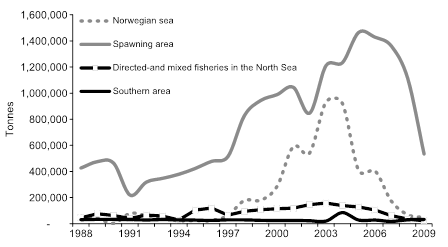

In order to achieve this dual perspective, Villasante uses a combination of official statistics including: fishing quotas, direct and indirect employment, reported catches, and the flows of goods and services. Where official statistics were unavailable interviews with local Galician fishermen and experts as well as information gathered by the Ministry of Industry, Commerce, and Tourism were used. Villasante also used traditional stock-catch plots (Figure 2) to assess the state of the fishery and several external indicators, such as the flow of goods and services, social and cultural patterns, number of fishing vessels, and tax data, to develop an economic model of how reductions in catch would affect the fishery as well as different sectors of the economy.

This approach is interesting to me because it allows for the integration of biological, economic and social aspects of a fishery. While I agree that interviews may be helpful in supplementing official data, it does make me wonder how reliable the calculations from those sectors will be since the data have been obtained from colloquial observations and unofficial experts rather than official fisheries management sources.

Biologically, the major theme of this paper is an idea of stock mismanagement due to poor information. Up until the 2011 International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES) Working Group of the Stock Identification Methods Working Group (SIMWG) report on this species’ genetic structure, the species was considered a single population. However, it appears that there are two separate breeding units, one to the north and one to the south (Figure 3) (Was et al. 2008). Villasante also categorizes the different sections of the fishery by levels of exploitation to determine whether they are overfished, developing, etc. (Figure 4). This way, he can try to determine whether one of the breeding stocks is being fished more than the other.

From the human side of the equation, Villasante concentrates on the economic importance of the fishery. The catches from the blue whiting fishery in Spain brings in an average of 12.8 million Euros per year (Villasante 2012). This does not include the value of the fishery in terms of employment, tax revenues, and values of goods and services. The figures relating to these factors were not presented in this paper, but I assume they must have been used as Villasante calculates the monetary loss in these sectors resulting from a 93% reduction in total allowable catches. This figure is used because the European Union recently adopted the 93% stock reduction to help bring back this stock from its recently observed decline. Overall, the projected total loss due to the new stock reduction, including reductions in revenue from the catch itself and reductions in revenue from other sectors, including tax revenue, is 40, 081, 636 Euros per year.

Moving on with his analysis, Villasante shows us the dangers of mismanagement. He states that without management based on the true genetic structure of a population, “extinction of subpopulations could occur before the analyses of aggregated data would indicate a population decline” (Villasante 2012).

I agree, given that fishing does not occur equally throughout the species’ entire range; it would make sense that a certain genetic population occurring in a heavily fished area would decline before another genetic population in an area that is not experiencing as much fishing.

Similarly, Villasante leaves us with a call to action on the human side of the equation, “The persistent lack of acceptance of humans as components of social-ecological systems is, in fact, artificial and arbitrary, and this should be reformulated to reverse current unsustainable paths” (Villasante 2012). This is a point I wholeheartedly agree with. Fishing itself is a human activity. In our management plans, we need to consider that humans are a part of the equation and will be affected by changes. This theme is best illustrated by the calculated economic losses throughout the entire economy. It is not only the fishermen themselves, but nearly the entire country that will feel at least some effect of management reforms.

Hopefully, Villasante’s call to action will be heard and there will be increased discussion of new data as well as the human aspect of fisheries at the next common Fisheries Policy reform. Additionally, I hope that fishermen will be included more in policy reforms. After all, the involvement of stakeholders in the decision-making process is vital to effective and fair fisheries management (Pomeroy 1995).

REFERENCES

Commission of the European Communities (2009) Green Paper—Reform of the Common Fisheries Policy, Brussels, 22.4.2009, COM 163.

Pomeroy, RS (1995) Community-based and co-management institutions for sustainable coastal fisheries management in Southeast Asia. Ocean Coast Management 27(3):143-62.

Was, A; Gosling, E; McCrann, K; Mork, J (2008) Evidence for population structuring of blue whiting (Micromesistius poutassou) in the Northeast Atlantic. ICES J Marine Science 65: 216—225

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!