2020 Shark Research and Conservation Highlights

2020 was a year for the books! While we were unable to conduct in-person research and outreach for most of the year, we developed new ways of advancing our research and engaging the public. Despite the challenges of 2020, we are proud of what we were able to accomplish and are excited to share some of the highlights with you:

- We published 9 research papers in scientific journals. These papers ranged in topics from evaluating spatial management options to conserve tiger sharks in the Western North Atlantic Ocean to describing the development of new satellite tagging technologies to remotely monitor animal activity levels across the ocean.

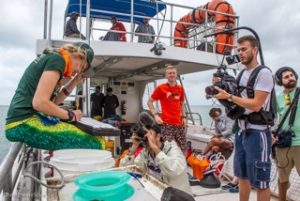

- In the first months of the year prior to COVID-19, our team brought over 413 Citizen Scientists, mostly school kids, on our research vessels to participate in our hands-on shark science. These participants were of diverse origins, representing 29 countries and another 33 states within America.

- We tagged 201 sharks, the smallest being a 1.6 ft spiny dogfish shark and the largest being a 15 ft great hammerhead shark.

- We deployed 37 acoustic tags and 8 satellite tags on sharks of various species, in both Florida and South Africa. We collected 245 vials of plasma, 179 muscle biopsies, and 97 fin clips.

- 17 of our sharks tagged with conventional ID tags were recaptured: 16 in the USA with 1 in South Africa! 3 of these sharks were originally tagged 6 years prior!

A satellite tagged shark

- We proudly launched a Diversity, Equity, & Inclusion committee comprised of undergraduate, graduate students, staff and faculty to promote racial diversity, equity, and inclusion within our lab and in the scientific community through innovative outreach.

- Our work was featured in three major television programs, including one show on National Geographic Australia (Save this Shark with Mick Fanning) and two shows on the Discovery Channel’s Shark Week (Monsters Under The Bridge and ShaqAttack).

- Our research program Urban Shark was featured on the NBC Today Show with Kerry Sanders. Sanders and his team joined us for a day of fishing off downtown Miami to witness firsthand how close sharks are to a metropolitan city like Miami.

- SRC’s Dr. Liza Merly was featured in international media discussing squalene from sharks and the development of the COVID -19 vaccine.

- Our social media platforms connected new audiences, with our Instagram reaching 47,200 total followers, our Twitter reaching 6,217 followers, and our Facebook page reaching over 15,427 followers.

- We launched a new way for our audiences to engage in science, through “Little Moe” – a new social media platform. Follow Little Moe FB: @LittleMoeShark twitter/insta: @LittleMoe_Shark

- Four SRC students defended their thesis, including MS student Mitchell Rider, Elana Rusnak, Chelsea Black, and Trish Albano.

- We presented at 7 conferences and virtual speaking engagements, including Capitol Hill Ocean’s Week and the American Elasmobranch Society Annual Meeting.

- Despite the significant impact of COVID-19, we were able to finish up our research at De Hoop nature reserve in South Africa.

Students deploying an underwater video in South Africa

- We participated in the first online version of the Rosenstiel School’s popular Women in Marine Science Day for middle school and high school girls. Over 300 girls attended from schools across the country.

- We proudly continued collaborations with NOAA’s National Marine Fisheries Service to focus on conserving threatened species in the Biscayne Bay Habitat Focus Area. This culminated in a scientific publication documenting growing numbers of critically endangered smalltooth sawfish within coastal waters off Miami.

We are optimistic for 2021 and grateful to our donors, friends, collaborators, followers, and students.We are especially grateful to our active funders and contributors, notably the Batchelor Foundation Inc, Rock the Ocean Foundation, Ruta Maya Coffee, the Isermann Family Foundation, the Herbert W. Hoover Foundation, William J. Gallwey, III, Cannon Solutions America, H.W. Wilson Foundation, Interphase Materials, Waterlust, Hook & Tackle, the Ocean Tracking Network, Vineyard Vines, the Alma Jennings Foundation, the Shark Conservation Fund, the International SeaKeepers Society, Give Back Brands Foundation, NOAA, the Hefner Fund, and all generous individuals and groups who have Adopted a Shark.

Directed by Dr. Neil Hammerschlag, the Shark Research & Conservation Program (SRC) at the University of Miami conducts cutting-edge shark research while also inspiring scientific literacy and environmental ethics in youth through unique hands-on field research experiences. To impact an even larger audience from across the globe, SRC continues to use a variety of online education tools, including social media, blogs, educational videos and, online curricula. SRC’s science focuses broadly on understanding the effects of environmental change on the behavioral ecology and conservation biology of sharks in a human‐altered world. To learn more, visit www.SharkTagging.com

![A Varela High student helps insert a mark-recapture tag into a nurse shark.]](https://sharkresearch.rsmas.miami.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/PIC-1-225x300.jpg)