Evaluating Extinction Risk in Major Marine Taxa

By Olivia Schuitema, SRC intern

Over Earth’s history, there have been at least five mass extinctions in addition to other minor-scale extinctions (Bambach et al. 2004). The causes of such extinctions are varied, but many be associated with global climate variability (Doney et al. 2012). One article points to large-scale volcanism associated with global warming, acid rain and ocean acidification for the causes of extinctions (Bond et al. 2017). This is especially significant in recent years, because of the large and rapid increase in global temperatures (largely due to the burning of fossils fuels and deforestation) and corresponding varied changes in climate. Thus, in order to understand and predict future extinctions patterns, we must understand past ones.

The paleontological record (fossil record), gives much insight on these extinction events, allowing the present to look at past trends. In the effort to understand anthropogenic influence on modern marine biota, the fossil record can be analyzed and compared to the extant (living) groups (Carrasco et al. 2013). Thick fossil-rich marine sediments located around the world contain a plethora of information that can help prepare future extinction trends (Finnegan et al. 2015). These sediments (Figure 1) can give insight on particularly vulnerable taxa in potential danger of going extinct. Vulnerability among a population includes being threatened with a decline in numbers or genetic material, reduced fitness, or extinction (Dawso et al. 2011).

Fossils of various marine and terrestrial organisms are located in layers in the fossil record. The layers can give information on environmental conditions of the time and age of organisms (Wikimedia Commons).

A new study aimed to construct models of extinction risk and utilize them to evaluate baseline extinction vulnerabilities for some living marine taxa (Finnegan 2015). The article defines “extinction risk” as the probability of classifying fossil taxa as “extinct” based on its similarity to other extinct fossil taxa during the same time (Finnegan et al. 2015). The timeline used in the analysis was from the Neogene period to the Pleistocene period, encompassing about 23 million years in total. This time period was chosen to maximize faunal and geographic comparability (Finnegan et al. 2015). Some groups of organisms (taxa) found in this time interval are still living today and have similar geographical distributions as they did in the past. These similarities make it easier to compare marine taxa over varying conditions to help determine intrinsic risk. “Intrinsic risk” as used in the article, is the term for baseline vulnerability for marine taxa.

Six major marine taxonomic groups, including bivalves, gastropods, echinoids, sharks, mammals, and scleractinian corals were analyzed in this study (Finnegan et al. 2015). These groups were chosen for their relatively accurate representation of overall marine ecological, taxonomic, and functional diversity. The two best predictors for extinction risk are geographic range size and taxonomic identity (Finnegan et al. 2015). The predictors of extinction found in previous paleontological models (including geographic range size, latitude, etc.), were measured for the six marine taxa. Results indicate that the geographic area with the highest intrinsic risk was the tropics, especially the Indo-Pacific and the Western Atlantic (Finnegan et al. 2015). Similarly, another study highlights the increased extinction rates of North American mammals. Results showed a diversity crash in parts of North America during the Holocene Epoch (Carrasco et al. 2013). Although this mammalian extinction occurred later than the time period analyzed in the work of Finnegan et. al (2015), the geographic locations are similar, supporting the overall increasing extinction trend over time.

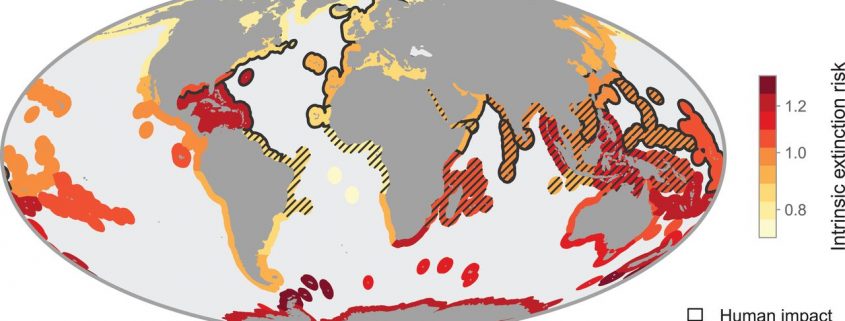

Another modeling system analyzed the hotspots for human activity and climate change velocity in contrast to the areas of high extinction risk of the six major marine genera (Finnegan et al. 2015). The results as seen in Figure 2, show that hotspots of anthropogenic influence and high climate change velocity overlap the areas of highest extinction risk (Finnegan et al. 2015), indicating a correlation between humans, climate change and extinction risk. The areas of overlap were mostly concentrated in the tropics and the subtropics. The tropics contain very high levels of biodiversity, providing habitat for unique species found nowhere else in the world. This is especially true for marine organisms. Conserving this diverse environment is important because of the many ecological services and economic benefits it provides.

Hotspots of anthropogenic impact and velocity of climate change overlaid on mean intrinsic risk (Finnegan et al. 2015).

The term “global warming” has evolved into the term “climate change” because of the new understanding of the changes in overall climate (weather patterns, natural disasters, sea level rise, etc.), and not solely an increase in global temperatures. Climate change has a variety of extinction-inducing mechanisms including ocean acidification, anoxia (lack of oxygen) and global warming (Bond et al. 2017). The variability of these factors puts stress on organisms, causing them to migrate or to die out if they cannot adapt quickly enough. Thus, the coupled effects of climate change and human activity on highly diverse environments can cause increased extinction vulnerabilities among taxa (Finnegan et al. 2015). This possible loss of biodiversity and evolutionary potential must be taken seriously (Dawson et al. 2011).

Works Cited

Bambach, R. K., Knoll, A. H., & Wang, S. C. (2004). Origination, extinction, and mass depletions of marine diversity. Paleobiology, 30(4), 522-542.

Bond, & Grasby. (2017). On the causes of mass extinctions. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 478, 3-29.

Carrasco, Marc A. (2013). The impact of taxonomic bias when comparing past and present species diversity. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 372, 130.

Dawson, T., Jackson, S., House, J., Prentice, I., & Mace, G. (2011). Beyond Predictions: Biodiversity Conservation in a Changing Climate. Science, 332(6025), 53-58.

Doney, S. C., Ruckelshaus, M., Duffy, J. E., Barry, J. P., Chan, F., English, C. A., … & Polovina, J. (2011). Climate change impacts on marine ecosystems.

Finnegan, S., Anderson, S., Harnik, P., Simpson, C., Tittensor, D., Byrnes, J., . . . Pandolfi, J. (2015). Extinctions. Paleontological baselines for evaluating extinction risk in the modern oceans. Science (New York, N.Y.), 348(6234), 567-70.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!