Impending bloom: Human impacts on the marine environment

by Stacy Assael, RJD intern

Ever wonder how mankind has contributed to the increase of jellyfish? Well, a recent study by Carlos Duarte et. al. (2012) has suggested that the large amounts of man-made structures/materials popping up in our world’s oceans may be providing artificial substrates for jellyfish polyps to attach to. Prior research on this subject matter has primarily focused on the adult stage of a jellyfish’s’ life cycle, and has attributed the increased occurrence of jellyfish blooms to a decrease in predation, climate change, and higher concentrations of nutrient rich water.However, this study indicates that man’s contribution is happening sooner in the jellyfish life cycle rather than later.

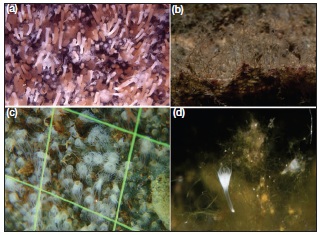

Figure 1 from Duarte et al. 2012. “Photographs of jellyfish polyps attached to artificial structures. (a) Strobilating polyps of Aurelia labiata attached to a marina float in Cornet Bay, Washington State (5 cm × 7 cm; from Purcell et al. 2009); (b) hydroids of Obelia dichotoma attached to plastic debris in the Ebro Delta, Spanish Mediterranean; (c) polyps of A aurita attached to a floating pier in the Inland Sea of Japan (2.3 cm × 3 cm); and (d) polyp of Cotylorhiza tuberculata attached to sunken piers in abandoned aquaculture concessions in the Mar Menor, Spanish Mediterranean.”

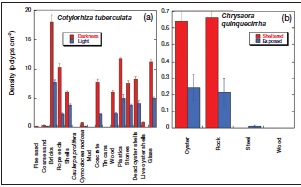

For this experiment, two different species of jellyfish, Chrysaora quinquecirrha, native to the Chesapeake Bay, and Cotylorhiza tuberculata, primarily found in the Mediterranean Sea, were exposed to different artificial and natural substrates. When exposed to the variety of materials, polyps showed a preference for artificial substrates. The results of this experiment are consistent with observational studies off the coast of Europe and Asia which show polyp colonies exceeding numbers of 10,000 individuals per meter squared on manmade structures.

Figure 2 from Duarte et al. 2012. “Experimental assessment of jellyfish planula settlement on different substrates for (a) Cotylorhiza tuberculata from the Mediterranean Sea and (b) Chrysaora quinquecirrha from Chesapeake Bay. Bars represent mean ± standard error polyp density on different substrates and conditions (red and blue bars). Settlement differed significantly among substrates for both species (ANOVA, P < 0.0001; WebTable 1). Settlement of C tuberculata was highly successful on hard substrates, particularly on smooth artificial surfaces including glass, plastic, or bricks, and in the dark (ANOVA, P < 0.0001; WebTable 1). Numbers of C quinquecirrha polyps were similar on oyster shells, their natural habitat, and stones (t test, P = 0.97) and significantly higher (t test, P < 0.005) on recruitment panels spaced closely to exclude large predators as compared with more exposed panels. “

These results spark concern due the large increase of aquaculture pens, docks, seawalls etc. in our coastal waters. Artificial structures such as these appear to be playing a more pivotal role in areas comprised of mostly soft sediments which are not conducive to jellyfish polyp attachment. In addition to providing a place to adhere, these structures are also sheltering the young jellyfish from the harsh marine conditions. Therefore, more jellyfish are able to survive into adulthood.

It would be useless to suggest that humans abandon our outward expansion into the marine environment. However we must find a creative solution that is advantageous to man without disrupting the natural order of the underwater ecosystem. Although this is a bold statement, small modifications such as altering the design of coastal structures and reducing the amount of plastic waste in the ocean may reduce the occurrence of jellyfish blooms.

References

Duarte, C. et al. (2012). Is global ocean sprawl a cause of jellyfish blooms? Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!