How the geographic range characteristics of a species can affect its conservation

By Elana Rusnak, SRC intern

For many of us scientists, our end goal is conservation of our target species. But what does this mean, and how do we reach these goals? Unfortunately, the answer to this question is not cookie-cutter and requires the input of multiple factors that are not so easily or frequently studied.

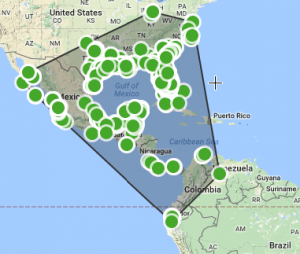

At the largest scale, the two broad measurements of geographic range can either provide too much or too little area to be taken into account with regards to protecting a certain species: the extent of occurrence (EOO) and the area of occupancy (AOO). The area of occupancy is all the local area in which a species has been recorded, but only accounts for those localized areas. It may not take into consideration the other hospitable habitat in which individuals simply haven’t been recorded yet. The extent of occurrence is generally larger; as it encompasses all of the area a species could possibly live in, including the space between the recorded individuals (Gaston, 1991). The debate between area of occupancy and extent of occurrence may yield different results, which could cause complications especially with policymakers. While it may seem ideal to cover as much habitat as possible in order to protect a species, it is expensive and requires a lot of enforcement, therefore making it difficult for policymakers to go only on extent of occurrence, since it might include habitat in which the species does not ever reside. However, it also might include area in which a species is migrating, but only during a small part of the year. Why would they want to spend valuable resources to protect an area that does not need to be protected? For example, the White Ibis has year-round populations along the coast of the southern United States and Mexico, as well as a population in northern South America. They are migratory birds, and spend part of the year more inland in the United States, yet it is only a few months of the year (The Cornell Lab of Ornithology, n.d.). If these birds were to become endangered, it is likely that there would be conflicts in determining how much of the yearly range should be protected and why.

The area of occupancy of the White Ibis (Eudocimus albus) (http://geocat.kew.org/editor)

The extent of occurrence of the White Ibis (Endocimus albus) (http://geocat.kew.org/editor)

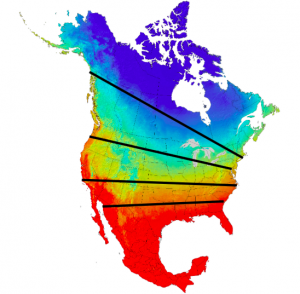

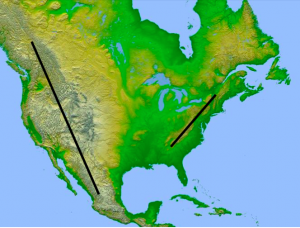

Another factor determining the geographic range is it’s shape. The shape of the geographic range generally constrained from the North and South, or from the East and West. North-South constraints are frequently controlled by the macroclimate (ex. temperature and precipitation), whereas East-West constraints are controlled by topography and availability of suitable habitat (Brown et al., 1996).

Habitat controlled by macroclimate, creating North-South constraints

Habitat controlled by topography, creating East-West constraints

A problem in present times stems from climate change, which may alter the range shape due to rising temperatures. If a northern bird’s climate suddenly becomes too warm to endure, they may move north in order to compensate. If they were protected in their original habitat, however, the protected area may not cover their new habitat, which may result in population losses. A study done by Møller et al. in 2002 indicates just that: rapid climate changes are associated with dramatic population loss of migratory birds in the Northern Hemisphere. This can be a difficult situation for policymakers, especially if the population is both moving and declining at rapid rates.

Brown et al. further describes the issues of range size and boundary by commenting on the fact that the range edge is never defined. The internal populations of a geographic range tend to be steadier, with larger, constant populations. However, the outer edges of the range are mercurial, which makes it very difficult to determine. This brings us back to the extent of occurrence vs. area of occupancy issue. While individuals are seen at the borders of ranges, or in an excluded area, it does not necessarily mean that they are within the “geographic range” of their species. Since the edges change constantly, policymakers generally need to decide if they want to protect the bulk of the population, or the entire area that they cover.

At the smallest of scales, genetics also plays a role in conservation. While species can change and evolve into different species over very long periods of time, the genetic analysis tools we have today can show that what we thought was one species is actually two. For example, the California newt (Taricha torosa) was divided into two species in 2007. The newts living on the coast keep their Latin name, while the separate species living in the sierra has been named Taricha sierrae. (Kutcha, 2007). Modern speciation events like this can also have an effect on policy. If both species are endangered, policymakers would need to protect both species instead of just the one beforehand, which leads to more money spent and another proposal to be passed.

It is no wonder, now, that policymakers take so long to get a species protected. The factors discussed above are only a few of the considerations they must take into account in order to pass a proposal supporting protecting part of, or the entire geographic range of a species. With all that being said, every bit of science contributing to conservation is important science, which is why we do it.

Literature cited

Brown, J. H., Stevens, G. C., & Kaufman, D. M. (1996). The geographic range: size, shape, boundaries, and internal structure. Annual review of ecology and systematics, 27(1), 597-623.

Gaston, K. J. (1991). How large is a species’ geographic range?. Oikos, 434-438.

Møller, A. P., Rubolini, D., & Lehikoinen, E. (2008). Populations of migratory bird species that did not show a phenological response to climate change are declining. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105(42), 16195-16200.

Shawn R. Kuchta (2007). “Contact zones and species limits: hybridization between lineages of the California Newt, Taricha torosa, in the southern Sierra Nevada”. Herpetologica. The Herpetologists’ League. 63 (3): 332–350. doi:10.1655/0018-0831(2007)63[332:CZASLH]2.0.CO;2.

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology. (n.d.). White Ibis. Retrieved March 25, 2017, from https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/White_Ibis/id