SRC Highlights in 2019

/in SRC blog /by aanstettUM SRC had a productive 2019. Here are some of the highlights we are proud to share with you.

- We published 13 research papers in scientific journals. These papers ranged in scientific topics from determining the ecosystem consequences of shark declines to determining the extent to which sharks are under threat from commercial fishing.

- Two of our research papers were featured on the covers of scientific journals, viewed below.

![]()

- We spend nearly 250 days in the field conducting research. This included research in Miami, Bahamas and two new locations in South Africa.

- Our team brought over 1,600 Citizen Scientists, mostly school kids, on our research vessels to participate in our hands-on shark science. These participants were of diverse origins, representing 45 countries and another 42 states within America.

- We were again proud to run several of our special F.I.N.S trips (Females in the Natural Sciences), providing inspirational research experiences to young girls.

- We proudly hosted a group of war veterans from USX on our boats to participate in a day of shark research.

- This past year our team tagged and sampled 575 different sharks of 19 different species, including 35 great hammerheads, 23 bull sharks, and 43 tiger sharks. The largest shark we tagged was a 400 cm (13 ft) great hammerhead shark in the Bahamas and the smallest was a 56 cm (1.8 ft) smooth hammerhead shark in South Africa.

- Our team was able to satellite tag 14 sharks as well as acoustically tag another 52 sharks, including 6 new species as part of a new project in South Africa (Puffadder shyshark, spotted gully shark, leopard catshark, smooth hammerhead shark, pyjama catshark and dark shyshark).

- Our SRC team spoke to thousands of people in various outreach events, including exhibiting a booth at the Tortuga Music Festival and traveling to Ohio to speak to high schools. MS student Chelsea Black traveled to Saba Island in the Dutch Caribbean to give an invited series of lectures to the public.

- Our team presented scientific talks at several national and international conferences, including PhD student Laura McDonnell who contributed to a workshop at the OceanObs conference in Hawaii and MS student Mitchell Rider who presented a poster at the 5th International Conference on Fish Telemetry in Norway. SRC Director Dr. Neil Hammerschlag also presented a keynote address at the 5th International Whale Shark Conference in Exmouth, Australia.

- Our research reached millions of people through exposure in prominent media outlets, including three shows on Discovery Channel’s Shark Week (Air Jaws Strikes Back and Andrew Mayne: Ghost Diver).

- We held our third annual Summer Research Program, where college students from across North America spent several intense weeks with us in the field and laboratory conducting research.

- This past year we also provided two new college credit-bearing summer courses for high school students participating in the University of Miami’s Summer Scholars Program. This included a lecture-based shark biology course taught by Dr. Hammerschlag and a practical hands-on course based in the lab and field.

- Several SRC students defended their thesis, including MS student Shannon Moorhead, who will be working as a new technician in our lab in 2020.

- Hammerschlag was awarded a collaborative grant supported by the National Oceanographic Partnership Program to study marine biodiversity in the Florida Keys as part of the Marine Biodiversity Observation Network (MBON).

- Our social media platforms connected new audiences, with our Instagram reaching 40,000 total followers, our Twitter reaching 5,500 followers, and our Facebook page reaching over 14,600 followers. Across platforms, each of our posts are reaching an average total readership of 200,000 people.

- We proudly continued collaborations with NOAA’s National Marine Fisheries Service to focus on conserving threatened species in the Biscayne Bay Habitat Focus Area.

- We expanded the depth of our research, such as our projects on Urban Sharks, White Shark Predatory Behavior, Evaluating the Efficacy of Marine Reserves for Threatened Sharks, and Ecosystem Impacts of Overfishing.

We are grateful to our active funders and contributors, especially the Batchelor Foundation Inc, Rock the Ocean Foundation, Ruta Maya Coffee, the Isermann Family Foundation, the Herbert W. Hoover Foundation, William J. Gallwey, III, Cannon Solutions America, H.W. Wilson Foundation, the Disney Conservation Fund, Interphase Materials, Waterlust, Hook & Tackle, the Ocean Tracking Network, Vineyard Vines, the Alma Jennings Foundation, the Shark Conservation Fund, the International SeaKeepers Society, Give Back Brands Foundation, NOAA, the Hefner Fund, and all generous individuals and groups who have Adopted a Shark.

Directed by Dr. Neil Hammerschlag, the Shark Research & Conservation Program (SRC) at the University of Miami conducts cutting-edge shark research while also inspiring scientific literacy and environmental ethic in youth through unique hands-on field research experiences. To impact an even larger audience from across the globe, SRC continues to use a variety of online education tools, including social media, blogs, educational videos and, online curricula. SRC’s science focuses broadly on understanding the effects of environmental change on the behavioral ecology and conservation biology of sharks in a human‐altered world. To learn more, visit www.SharkTagging.com

Thanks to the SRC team, collaborators, and supporters for another incredible year, and let’s make 2020 even better.

The Role of Macroalgae in the Ecosystem

/in SRC blog /by adminBy Haley Kilgour, SRC intern

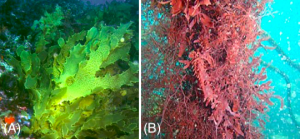

Seaweeds are well-known to be important primary producers in coastal waters, but they may potentially also play a role in providing refuge from ocean acidification. Macroalgaes such as Laminariales and Fucales, both of which are brown algaes, are ecosystem engineers that influence factors such as water velocity, light penetration, and chemical characteristics of seawater (e.g. via carbonate chemistry, and oxygen and nutrient availability).

Figure 1. A) Ecklonia radiata. B) ephiphyte. While epiphytes come in many shapes and sizes, ranging from looking like hair and snot, to being delicate and flowerlike, they normally grow on top of another plant. Note the epiphyte shown in B is not the epiphyte found on Ecklonia radiata in this study.

The diffusive boundary layer (DBL) exists at the surface of the leaf blade and is the area of the most rapid and variable fluctuations. The DBL is formed when a fluid moves over a solid and no-slip conditions create a region of viscously-dominated laminar flow. Here movement of ions and molecules is by molecular diffusion and the metabolic activity of the organism, in this case, seaweeds, creates a concentration gradient from the uptake and release of dissolved substances to and from the surface of the leaf blade. DBL microenvironments are not only important in the transfer of nutrients and metabolites but are also critical for timing of gamete release and keeping antifouling agents at the blade’s surface. Many organisms such as bacteria, diatoms, various larvae, annelids, and other algae live in this layer.

Over the next century the pH of seawater, on average world-wide, is expected to be reduced by 0 .1-0.3 units. While this change seems to be small, this is in fact quite drastic and will greatly impact corals and their ability to pull calcium carbonate from the water, which is the major component of their exoskeletons. The goal of this study, from Noisette and Hurd (2018), was to: a) study the characteristics of thickness and concentration gradient of DBL at the blade surface of Ecklonia radiata and b) determine the characteristics of DBL in predicted future conditions.

Eighty blades of algae were taken from in situ locations in Hobart, Tasmania, Australia. In the lab, the blades were kept at 13°C and in low light conditions. Different combinations of light, mainstream pH, flow, and epiphytic conditions were evaluated with four blade replicates. Data was then analyzed for significance using three-way ANOVAs with pH, flow, and presence/absence of epiphytes. A three-way MANOVA was then used to compare coefficients of curves fitted to the profiles.

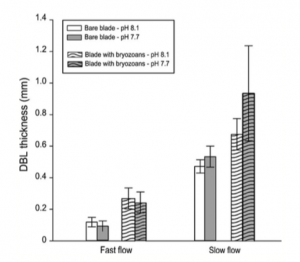

Figure 2. Shows DBL thickness in various treatments of pH, presence of epiphytes, and flow rates.

It was found that pH did not affect DBL while flow and epiphyte presence did. DBL was thicker in slow flow conditions, as well in epiphytic conditions. It was also found that oxygen profiles were steeper in fast flow treatments. Noisette and Hurd also found that epiphytes decreased the oxygen content of the DBL under dark conditions.

It was noted in particular that DBL thickness increased in slow flow because the DBL of the blade and epiphytes actually merged. Metabolic activity of both epiphytes and algae led to variations in oxygen concentration and pH in the DBL which offers potential refuge from future ocean acidification. While blades with epiphytes did have larger DBLs, net photosynthesis was lower due to epiphytes using oxygen produced by the algae and potential shading of the algae that might reduce the efficiency of photosynthesis.

Noisette and Hurd mention that organisms that regularly encounter strong fluctuations, like nearshore algae, might be better able to survive a lower pH of seawater due to higher phenotypic plasticity. DBLs might thus act as refuges for calcifiers and other organisms by allowing them to adapt to lower pH conditions over time. While this offers some room for adaptation of important oceanic organisms, it comes on a small scale. This could be the difference between complete breakdown of ecosystems and hanging on by a thread.

Work Cited

Noisette F & Hurd C. (2018). Abiotic and biotic interactions in the diffusive boundary layer of kelp blades create a potential refuge from ocean acidification. Functional Ecology, 32.5: 1329-1342.

North Atlantic right whales and the dangers and effects of entanglement

/0 Comments/in SRC blog /by aanstettBy Haley Kilgour, SRC intern

Mysticetes (baleen whales) arguably fall under the category of charismatic marine megafauna, capable of drawing the public’s attention to their conservation concern. However, many species are in quite a bit of trouble. Injury and mortality from entanglement with fishing gear is a problem that affects whales worldwide (Knowlton et al, 2016). It is perhaps one of the greatest concerns for the North Atlantic right whale, and is the second largest leading cause of death (Knowlton and Kraus, 2001). With only about 500 individual North Atlantic right whales left (Stills, 2017), conservation is urgently required to ensure the survival of the species.

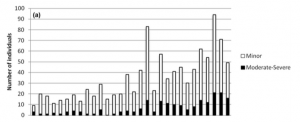

Number of North Atlantic right whales with minor or moderate-severe entanglements (Knowlton et al, 2016).

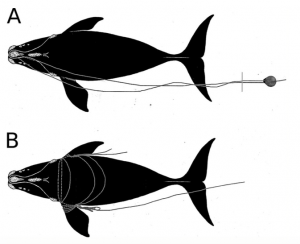

Much of the conservation for these whales surrounds lessening the amount of entangled gear on the whales that have already been entangled and lessening the amount of gear in which they may get entangled. Thus far, the United States has had limited success (Stills, 2017) and observed deaths of both right and humpback whales have exceeded the potential biological removal levels defined by the United States government (Knowlton et al, 2016). Figure 1 depicts the increasing number of North Atlantic right whales that are becoming entangled. While minor entanglements make up the majority of entanglements, the increasing number of moderate-severe entanglements is also increasing. With so few individuals remaining, every death is devastating. Deaths from entanglement are caused from instantaneous drowning, delayed death from impaired feeding, increased energy demands due to the drag of gear, and stress (Knowlton et al, 2016). Figure two shows in depiction A) a whale that would experience impeded feeding and in depiction B) a whale that would experience increased swimming efforts due to the drag of gear. Pettis et al (2014) found that stress responses to entanglement can affect the health of a whale even after gear has been removed. Van der Hoop et al (2013) found that entangled gear increased the power requirements of North Atlantic right whales by 70-102%.

Two possible configuration of gear on entangled North Atlantic right whales. Dashed lines are used to depict line on the underside of the animal (Van der Hoop et al, 2016).

The current efforts have focused on the reduction of rope within the water column (Knowlton et al, 2016). Knowlton et al (2016) studied the effects of fishing rope strength on large baleen whales, focusing on North Atlantic right whales and humpback whales. The purpose of the study done by Knowlton et al (2016) was to analyze the properties of ropes removed from whales and to examine rope characteristics in relation to species, age, and injury severity. Knowing rope deterioration rate and breaking strength is important because a certain amount of drag from entangled gear can be used by a whale to free itself (Van der Hoop et al, 2016), thus this knowledge can be used to create reduced breaking strength ropes that can effectively be used for fishing but will lessen the morality of large baleen whales.

Gear samples analyzed in this study were recovered by the Atlantic Large Whale Disentanglement Network, with most samples being taken from free-swimming or anchored entangled whales (Knowlton et al, 2016). The gear was assessed for the following characteristics: diameter, material and fiber type, condition, estimated breaking strength, and strength of a new rope of the same type and diameter (Knowlton et al 2016). The severity of entanglement and the configuration of the gear, for the most part, were assessed by photographs (Knowlton et al, 2016).

Per each whale used in this study, there was an average of 1.83 ropes and the condition of the rope for the majority of cases was classified as good to very good (Knowlton et al, 2016). The average breaking strength of rope entangling a North Atantic right whales was 19.30 kN, for humpback whales was 17.13 kN, and for minke whales was 10.47 kN (Knowlton et al, 2016). Knowlton et al (2016) found no adult North Atlantic right whales entangled in ropes below a breaking strength of 20.02 kN, which suggests that they can break free or disentangle themselves from the weaker ropes.

Several of the most dangerous aspects of entanglements for whales are infections caused by the rope cutting into their bodies, increased demands in energy requirements of swimming, and restricted feeding (Van der Hoop et al, 2016). Knowlton et al (2016) suggest that the use of reduced breaking strength rope could reduce mortality. While entanglements may not be prevented, the stress and numbers of mortality could lessen if ropes are easier for the whales to break free from. Knowlton et al (2016) do note that reduced breaking strength ropes would not prevent lethal entanglements in some areas such as calving grounds. Thus a conservation plan that reduces gear on already entangled whales, reduces the amount of gear in the water, and enforces use of reduced breaking strength ropes will be the most effective.

Works Cited

Hoop, Julie M. Van Der, et al. “Drag from fishing gear entangling North Atlantic right whales.” Marine Mammal Science, vol. 32, no. 2, Sept. 2015, pp. 619–642.

Hoop, Julie Van Der, et al. “Behavioral impacts of disentanglement of a right whale under sedation and the energetic cost of entanglement.” Marine Mammal Science, vol. 30, no. 1, 2013, pp. 282–307.

Amy Knowlton, and Scott Kraus. “Mortality and serious injury of northern right whales (Eubalaena glacialis) in the western North Atlantic Ocean.” Journal of Cetacean Research Management, no. 2, 2001, pp. 193–208.

Knowlton, Amy R., et al. “Effects of fishing rope strength on the severity of large whale entanglements.” Conservation Biology, vol. 30, no. 2, Jan. 2015, pp. 318–328.

Pettis, Heather M, et al. “Visual health assessment of North Atlantic right whales (Eubalaena glacialis) using photographs.” Canadian Journal of Zoology, vol. 82, no. 1, 2004, pp. 8–19.

Stills, Jennifer, editor. “North Atlantic right whales in danger.” Science, 10 Nov. 2017, pp. 730–731.

17 things the SRC accomplished in 2016

/0 Comments/in SRC blog /by a.anstett

It’s been a great year for our team! Here are some of our accomplishments from 2016:

1. We published 15 research papers in scientific journals on a variety of topics

2. Two of our research papers were featured on journal covers, one in Diversity and Distributions that evaluated the effectiveness of marine protected areas for migratory sharks and the other one in Animal Conservation that reviewed shark conservation and management policy tools

3. We brought 1,061 guests from the public out with us on our boats to participate in hands-on shark research. Participants ranged in age from 10 to 70, and originated from 42 U.S. states and 42 countries across the world.

4. Our team spoke to thousands of elementary, middle, high school and college students in their classrooms about marine biology and conservation! In one day we presented to about 1000 elementary school students at Key Biscayne K8 School.

5. Our students presented at international scientific conferences, including 6 talks at the American Elasmobranch Society annual meeting that was held this year in New Orleans

6. Our research was featured in various media, including Discovery Channel’s Shark Week (Tiger Beach and Air Jaws: Night Stalker) as well as in National Geographic’s Shark Fest (Mega Hammerhead).

7. We conducted 80 field research trips and measured, sampled, tagged and released 358 sharks of 12 different species!

8. The smallest shark we tagged this year was a 75 cm nurse shark and the largest was a 396 cm great hammerhead.

9. Our director Dr. Neil Hammerschlag gave a radio interview on NPR’s Fresh Air about sharks that was heard by millions of people.

10. We deployed 27 satellite tags on sharks! You can track all of our satellite tagged sharks online here! Special thanks to all the generous people who adopted sharks!!

11. We launched a new project in collaboration with Beneath the Waves and supported by Oceana in partnership with Google and Skytruth to utilize a first-of-its kind combination of satellite tagging and real-time mapping of fishing vessels on the high seas via Global Fishing Watch

12. Our team proudly exhibited in public events, including Taste of the Sea, Art Walk Miami and the Tortuga Music Festival!

13. Our tiger shark research in the Bahamas was included in a story in National Geographic Magazine

14. We partnered with the amazing brand Hook & Tackle on our new official team performance field shirts. They are now available for purchase online and through select retailers

15. Our Director, Dr. Neil Hammerschlag, co-founded and launched a new initiative called Digital Life, which aims to preserve the heritage of life on Earth through creating and sharing high-quality and accurate 3D models of living organisms.

16. We graduated 3 Masters Students and 1 Ph.D. Student. Congrats Hannah Calich, Jake Jerome, Alison Enchelmaier, and Dr. David Shiffman.

17. We launched our new program called F.I.N.S (Females in the Natural Sciences) to provide girls with hands-on experience in marine science as shark research volunteers with SRC.

Directed by Dr. Neil Hammerschlag, the Shark Research & Conservation Program (SRC) is a joint initiative of the Abess Center for Ecosystem Science & Policy and Rosenstiel School of Marine & Atmospheric Science at the University of Miami.

Thanks to the SRC team, collaborators, and supporters for an amazing year!

Meet Our Team: Emily Rose Nelson

/0 Comments/in Shark Research, SRC blog /by aanstett1. What’s your role in the lab?

Hey guys, I’m Emily! I’ve been working with the Shark Research Team at the University of Miami for about 4 years now. During my time with the RJ Dunlap program I have been involved with a number of projects. I have been the shark satellite tracking coordinator since 2013. I am responsible for keeping track of all our satellite tagged sharks. Nightly, I receive emails that indicate which of our sharks have transmitted throughout the day. Using a number of different databases I can then examine the location and movement of animals. From here, the tracks are updated on our website so the public can view the animal’s movement in near real time. The information we receive from these tags is used for numerous research projects going on in the lab to further enhance shark conservation. My current research involves looking at the movement patterns of tiger sharks and comparing it to a number of different morphological variables. In particular, we are trying to determine what exactly (i.e. tail size, body condition, reproductive status) determines how far, how fast, and where an individual will move.

2. Tell us a little about yourself.

I received my Bachelor of Science Degree in Marine and Atmospheric Science at the University of Miami, Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science in 2014 and will be starting work towards my Masters of Science in Marine Affairs and Policy with Dr. Hammerschlag in Fall 2015. Outside of the lab, I can probably be found tutoring (I love working with kids) or playing with my dogs and cats. I love avocados, water skiing, concerts, Blackhawks hockey, and driving across the Rickenbacker Causeway.

3. How did you get interested in marine biology and conservation?

For as long as I can remember I have wanted to spend my life working with the ocean and the amazing creatures within it, forcing me out of my land-locked home town of Chicago.

4. What’s your favorite part about working in the lab?

Working with the shark team at RSMAS has been one of the best experiences of my life. The adrenaline rush that comes after successfully completing a work up on a 350 centimeter tiger shark in the Bahamas is indescribable. Running statistical tests on a new set of data and finding a significant result is super exciting. However, the best part about being a member of this lab is the team I am surrounded by. It is an honor to work alongside some of the most talented and passionate people in the field. I am lucky to be able to learn something new from my colleagues every day and even luckier to call them some of my best friends.

Evolution of Motherhood: The Importance of Mature Female Fish

/1 Comment/in SRC blog /by aanstettBy Daniela Ferraro, RJD Intern

Older, female fish are becoming a necessity for the continuation of trophy-fish hunting and sustainable commercial fishing. Looking at both freshwater and saltwater species, the presence of larger, more mature fish increases the productivity and stability of fish populations. Dr. Mark Hixon, of the University of Hawai’i at Manoa, refers to the loss of big fish as “size and age truncation.” Big, old, fat, fertile, female fish, affectionately nicknamed BOFFFFs, have proved the ability to produce significantly more eggs than younger fish. They also can spawn at different times and places, allowing them the option of evading potential predators and threats to their offspring. Efforts to protect older, larger fish include creation of marine reserves, which act as no-take zones. Marine reserves allow fish to spawn throughout their entire lives. As large fish, BOFFFFs are a valuable commodity in commercial fishing, as fisheries tend to target marketable commodities. This specified targeting alters a fishery’s modes and methods: through the narrowing of mesh size or gear type. Drift nets and long lines are used in the removal of larger fish from certain populations. To some extent, even bait type and hook affects the type of fish caught. Slot limits are placed on commercial fisheries, limiting them to catching only medium-sized fish. Although egg size variation among a single species may be narrow, across a diverse range, significant maternal effects have been noted in terms of larger egg size.

BOFFFFs: Big (1.1m), old (ca.100 years), fat (27.2 kg), fertile female fish: Shortraker rockfish (Sebastes borealis). Image Source: Karna McKinney, Alaska Fisheries Science Center, NOAA Fisheries Service

More mature females produce more, and often larger, eggs that typically develop into larvae that can withstand more intense challenges like starvation and have a faster growth rate. This is partly due to the physical body size, as a larger fish translates to a wider body cavity to allow for the development of larger ovaries. BOFFFFs have a tendency towards earlier and longer spawning seasons. With this flexibility, these fish can withhold spawning in unfavorable conditions. Once the danger of predation, or other threats, has passed, BOFFFFs can spawn abundantly and improve recruitment. Hixon refers to this phenomenon as the storage effect. This ability is preferential when considering commercial and differential fishing. The targeted removal of BOFFFFs results in a truncation of size and age structure of a specific population. The removal of older fish from an overfished population will increase their probability of species collapse. The assumption that younger female fish contribute equally to production and stock is detrimental to the future of sustainable fishery stocks.

Fishery productivity would find stability in the implementation of old-growth age structures. Berkeley suggested three methods to limit the overfishing of BOFFFFs: slot size limits with both minimums and maximums, low rates of fishing mortality, and marine reserves. This can be accomplished with enforcement of both marine reserve no-take zones as well as catch limits. Marine reserves act not only as a direct safe place for fish to thrive and procreate, but also as a healthy influence on surrounding waters. They give maturing fish an area to develop, spawn and seed nearby fisheries.

Marine reserves act to provide ecosystems and environments for fish to not only reach sexual maturity, but past that. In addition, larvae from healthy marine reserves are found to seed the areas directly adjacent. This will assist in the replenishment of overfished and exploited populations. By integrating large-scale marine reserves, it is believed that it is possible to halt and reverse the decline of global fisheries while also protecting marine teleost, mammal, and invertebrate species. The decrease in mortality due to the protection of species by marine reserves and the subsequent increase in productivity has been seen in both temperate and tropical locations. Since marine reserves are located along reefs, estuaries, and kelp beds, it provides a large range in the protection of a diversity of species.

In a study conducted by Steven Berkeley et al, featuring 20 female black rockfish (Sebastes melanops), from five to seventeen years, it was found that larval groups from the older females grew three times faster than their counterparts. Larvae from the older fish also survived starvation twice as long. According to Berkeley, this is due to the provision of larvae with energy-rich triaglycerol (TAG) lipids as they increase in age. The TAG volume found in oil globules is positively correlated with age, growth rate, and survival. However, maternal effects can’t be classified as consistent across every species of teleost fish. Instead, research indicates that maternal effects have developed across a diverse taxonomic range. With the removal of matured female fish, populations are more likely to develop damaging consequences in terms of biodiversity and productivity.

References

Berkeley, Steven A., Mark A. Hixon, Ralph J. Larson, and Milton S. Love. “Fisheries Sustainability via Protection of Age Structure and Spatial Distribution of Fish Populations.” Fisheries 85.5: 23-32. Print.

Gell, Fiona R., and Callum M. Roberts. “Benefits beyond Boundaries: The Fishery Effects of Marine Reserves.” Trends in Ecology & Evolution 18.9: 448-55. Print.

Hixon, M. A., Johnson, D.W., and Sogard, S. M. BOFFFFs: on the importance of conserving old-growth age structure in fishery populations. – ICES Journal of Marine Science, 71: 2171–2185.

Can Facebook be used to increase scientific literacy?

/0 Comments/in SRC blog /by aanstettBy Sarah Hirth, RJD Intern

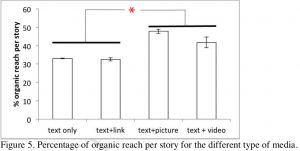

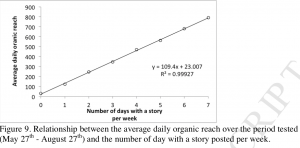

With the rising popularity in social media, more and more scientists are using social media platforms for education and outreach. The case study “Can Facebook be used to increase scientific literacy?” aims to investigate how effective Facebook is when it comes to educating people about the oceans.

Facebook is an excellent platform for fostering communication between scientists and citizens, thus also making it easier for experts to inform the general public about current issues. It has been observed that users find learning through Facebook fun, but how effective is this method as a platform for learning?

“Can Facebook be used to increase scientific literacy?” focuses on the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI). MBARI, is a private marine research institute that specializes in the innovation of technology for the purpose of studying the ocean.

Aiming to increase the number of people reached per post, MBARI decided to change their posting strategy. This included posting at different times, and changing the type of media posted along with a few other factors. The results and conclusions discussed in this case study, compare their new finding to their previous numbers. All data used in this case study came directly from MBARI’s Facebook page.

Although the change in posting strategy did not yield in an increased number of fans, MBARI was able to make some observations. One of the main observations was that stories posted with a photo or video reach 35.3% of the fans, whereas stories posted with only text, or a link will only reach 28.55%. Another factor in increasing the reach depended on the frequency of posts, where “the higher the number of days with a story in a week, the higher the average organic reach will be.” Although frequency was one of the observed factors, “if stories are posted five days a week, the days of posting only have a minor impact on the average daily organic reach.”

MBARI also found a correlation between the amount of words used and the number of people reached. However, most of their long texts were associated with photos, whereas short text was associated with links, thus making it difficult to argue that this had a direct impact on the reach. Apart from this, the data also showed that the organic reach on a given day increases by 18.26% if a story is posted the day before.

The final results showed that although Facebook can be a useful platform for raising user’s interest and giving them the opportunity to learn more, there is little opportunity for fans to develop their ocean literacy through social participation. This is due to the fact, that most Facebook users don’t follow the pages to engage in social practices. During this case study it was also observed that some people feel too uncomfortable or too insecure to comment on posts made by MBARI. However, once a user shares the story; their friends will be more comfortable and therefore more inclined to comment on posts. “The shared stories seem to be one of the main keys to increase participation and support the development of domain specific learning on Facebook.”

Shark Tagging with the University of Miami Alumni Association

/0 Comments/in Shark Research, SRC blog /by aanstettBy James Keegan, RJD Intern

Saturday’s trip looked like it would be a gloomy one with overcast and rain. I was excited for the catered trip, but I left for Crandon Marina with a sense of dread. The prospect of tagging sharks in choppy waters and cold rain did not thrill me. However, once the RJD team loaded the Diver’s Paradise, the skies cleared up a little. After Captain Eric and Neil went over safety and gear deployment, members of the Alumni Association and the RJD team introduced themselves. As we left for Soldier Key, the skies completely cleared, and I breathed a sigh of relief. The day was absolutely gorgeous.

With help from the Alumni Association, we deployed our gear quickly and took environmentals. We went for a brief swim, and afterwards Neil gave a great talk explaining our shark workup and the value of our research. With everyone now prepared, we returned to check our lines.

On our first line of the day we caught a nurse shark, and luckily for us, it was a fairly calm one. With help from members of the Alumni Association, we quickly performed the workup and released the nurse shark. We also caught nurse sharks on lines four and seven, but unfortunately, the nurse shark on four unhooked itself and swam away before we could get it on the platform. The shark on line seven had the largest head on a nurse shark that I have ever seen, and it was so feisty we did not bother trying to take blood. With three nurse sharks in the first set of lines, I was prepared for a long day filled with bruising battles. Nevertheless, I was content as the delicious catered lunch would sooth any pain.

However, my prediction was not correct as we only caught one more shark during the trip. A large lemon shark, about nine feet long, waited for us on the last line of the second round. Again, we quickly performed our workup and got the shark back into the water. I was glad members of the Alumni Association got a chance to feel the real roughness of sharkskin, because nurse sharks have comparatively smooth skin.

Lemon shark with pump. Caption: A member of the RJD team removes the water pump from the lemon shark’s mouth as we prepare it for release.

Although we did not catch any more sharks, our last catch of the day happened to be a barracuda in the third round of drumlines. We reeled it in and saved it to use as bait for the following day’s trip. Overall, we had a great day on the water, and I was glad alumni were able to come on board and participate in our research.

Cetacean Species Affected by Warming Arctic

/0 Comments/in SRC blog /by aanstettBy Hannah Armstrong, RJD Intern

Global climate change, among other anthropogenic issues, is becoming an increasingly significant threat to the Arctic region of the world. Specifically, higher average temperatures and rapidly disappearing sea ice are of conservation concern for ice-dependent species. Arctic marine mammals are specifically adapted to take advantage of the climatic conditions that have prevailed in the Arctic for millions of years, and have been a target of conservation based on their role in the functioning of Arctic ecosystems and surrounding communities. Despite these conservation concerns, with impacts of climate change likely to worsen in coming decades, there is increased industrial interest in Arctic areas previously covered by ice.

A graph showing the evident decline in average monthly arctic sea ice extent from September 1979 through 2012 (Reeves et al).

In a recent study, scientists observed and mapped the distribution and movement patterns of three ice-associated cetacean (marine mammal) species that reside year-round in the Arctic: the Narwhal (Monodon monceros), Beluga (white whale, Delphinapterus leucas), and Bowhead Whale (Balaena mysticetus) (Reeves et al. 2013). Then they used these ranges and compared them to current and future activity sites related to oil and gas deposits, exploration, development and commercial shipping routes, to assess areas of overlap, as a means of highlighting areas in the Arctic that might be of conservation concern. Some of the results indicated the sensitivity of Bowhead whales to industrial activity; the sensitivity of Narwhals to climate change and noise, as well as a shift in distribution due to ice conditions; and the sensitivity of Beluga whales to noise, as well as a wider distribution extending into the sub arctic (Reeves et al. 2013). These observations ultimately triggered the need for a better understanding of the implications of environmental changes in the Arctic for cetacean species, in order to develop effective conservation and management policies (Reeves et al. 2013).

Poorly documented shipping routes and operations, in addition to accelerating Artic pressures in Arctic Norway, Arctic Russia, the Alaskan Arctic, Arctic Canada and Arctic Greenland, indicate that immediate measures need to be taken to mitigate the impacts of human activities on these Arctic whales, as well as the people who depend on them (Reeves et al. 2013). As indicated by researchers, some of these measures include: careful planning of ship traffic lanes (re-routing if necessary) and ship speed restrictions; temporal or spatial closures of specified areas (e.g. where critical processes for whales such as calving, calf rearing, resting, or intense feeding take place) to specific types of industrial activity; strict regulation of seismic surveys and other sources of loud underwater noise; and close and sustained monitoring of whale populations in order to track their responses to environmental disturbance (Reeves et al. 2013).

After comparing maps of Arctic whale ranges with maps of recent and anticipated oil and gas activity and shipping traffic in the Arctic, researchers noticed the unquestionable overlap between Arctic whales and harmful human activities. Based on unparalleled current and predicted rates of climate change, the futures of these three Arctic whale species are uncertain. Based on the significance of these species, both culturally and for proper functioning of the Arctic ecosystem, well-informed management decisions related to human activities will be imperative going forward.

Reference:

Reeves et al. Distribution of endemic cetaceans in relation to hydrocarbon development and commercial shipping in a warming Arctic. Marine Policy 44 (2014).

“Narwhals Breach.” WikiMedia Commons. WikiMedia, 1 Oct. 2012. Web. 29 Jan. 2014.

Privacy Statement and Legal Notices

Copyright © 2018, University of Miami

All rights reserved.

4600 Rickenbacker Causeway

Miami, Fl 33149-1098

+1 305 421 4000